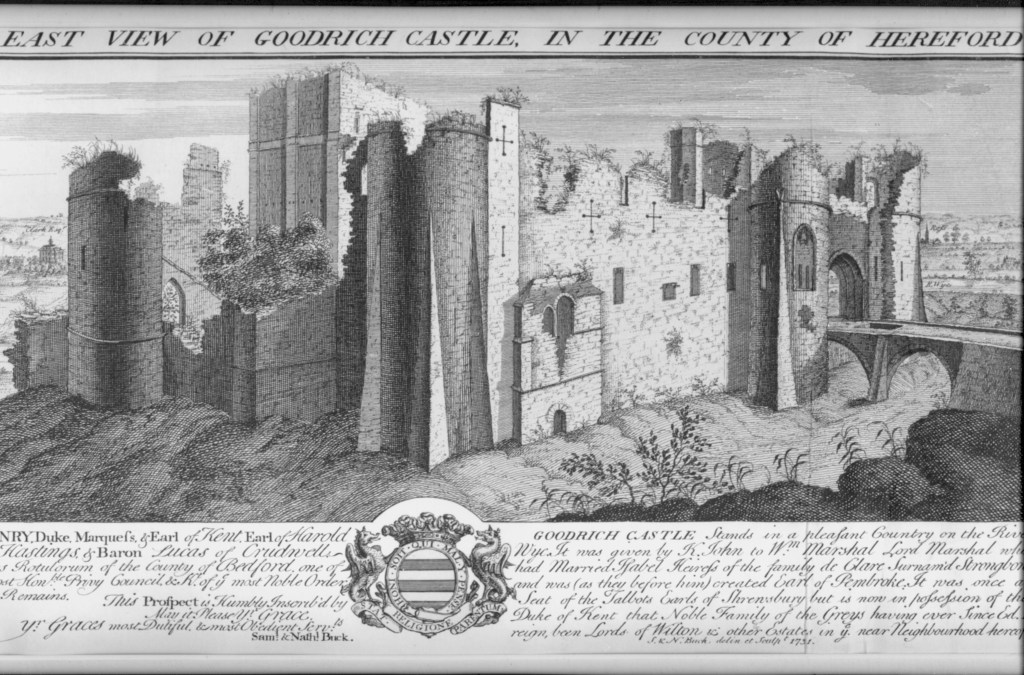

Reading Proust again returned me to some of my own past reflections on memory and self, the capital-S Self. A decade or so ago I spent considerable time reading in philosophy, physics, and neuroscience in an endeavor to get a grip on human consciousness and, perhaps, behavior. I posted about some of these texts on this here blog, in between writing about poetry, the garden, and my teaching job. Recent coincidences of reading returned me to this topic, “the hard problem of consciousness,” and made me consider how our embodied selves/minds/awareness: use shortcuts to manage the overwhelming inputs of our environments; define who we are using subjective if physically-based perceptions; and fail to see the obvious because of habituation and the apparent need to confirm what we believe we know. Illusions! The Vedic concept of Māyā, Plato’s Theory of Forms…propaganda, Penn & Teller, quantum physics, complexity theory, Marcel Proust, complementarity. I have a lot on my mind.

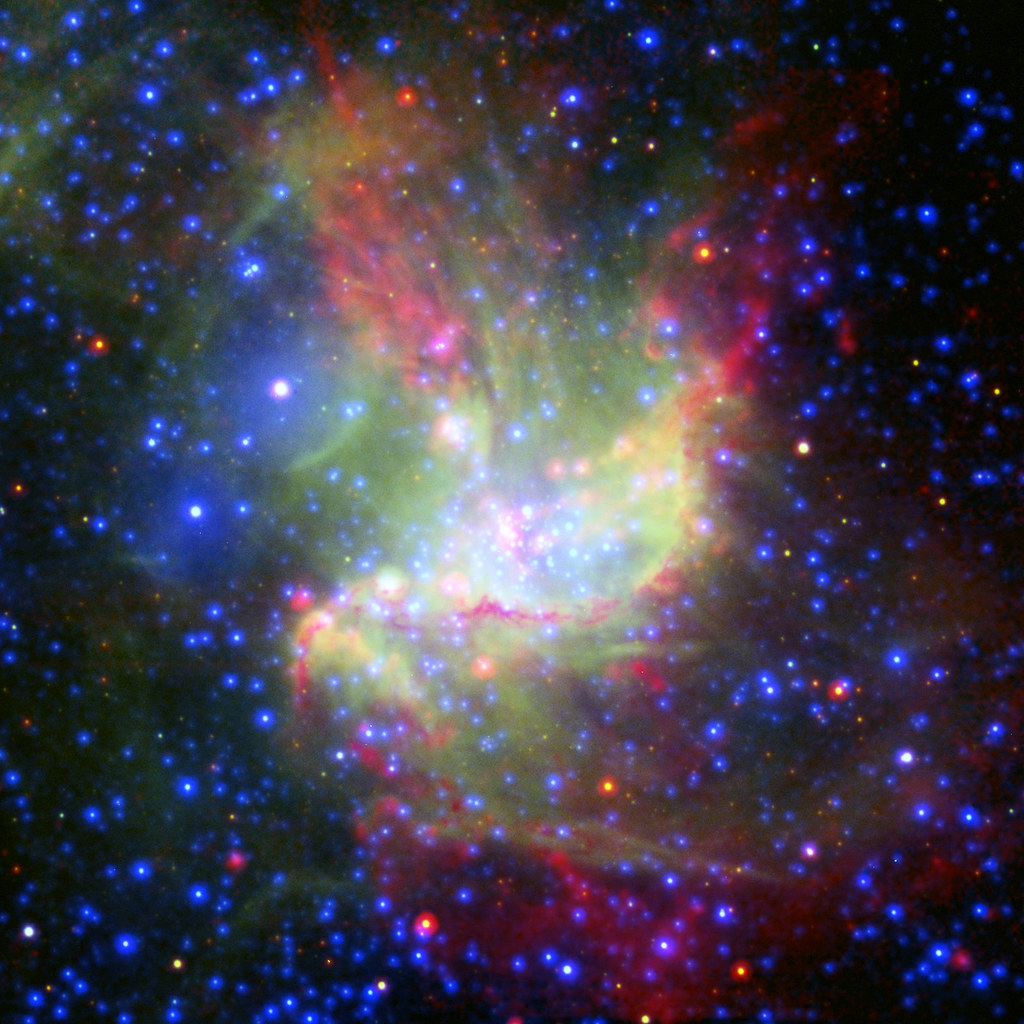

If it IS on (or in) “my” “mind.” For there’s even some question about that, as proposed by Neil Theise in his book Notes on Complexity. Just as light can be a wave or a particle, depending upon perspective and viewer (see: complementarity), it’s possible that our minds or selves can be individual and separate but also connected and boundary-less. The subtitle of this text is what appealed to me: “A Scientific Theory of Connection, Consciousness, and Being;” so far, I’m enjoying it and finding inspiration.

It’s needed, inspiration. Despite a few plunges into new drafts (see here), I have not been writing much for at least two months, and I miss it. The ideas from physics and neuroscience that intrigue me include potential metaphors and terms such as quenched disorder, endosymbiosis theory, and holarchy. These–along with the hard problem of consciousness–all have some relationship to complexity theory, and Theise does an elegant job of writing about complicated science concepts for the non-expert.

I ran across Notes on Complexity right after finishing Sleights of Mind, a book about the neuroscience behind the sort of illusion we call entertainment magic: sleight of hand, sawing people in two, mentalist “mind-reading,” and other performances; the authors, Susana Martinez-Conde, Stephen Macknik, and Sandra Blakeslee, are trying to discover more about how brains work (or filter, and sometimes don’t work so well) by studying how we get fooled by illusionists. This is a fun book, even more fun for me because one of my Best Beloveds has long been an enthusiast of magic shows and magicians. Martinez-Conde and Macknik are neurologists, so–unlike Theise’s text–this book is very body-mechanics in its basis. Their work reminded me of how amazing the human physiological system is. And it’s entertaining.

Before these non-fiction reads, I was finishing up with Proust who, in his own creative way, was exploring the interiority of the human self and carefully observing human interactions, behaviors, assumptions, prejudices, and aesthetics. Not neuroscience, because there is no science to it, but definitely related to how our brains and bodies process experience. My sense is that poetry works that that way for me: it’s not an abstract stream of thought but something inextricable from bodily experience, maybe even, through the environment in which we exist, something deeply connected to everything, a global being-there.

The way we process experience (and is this consciousness?) is largely what leads us to the arts, to make art or to appreciate it, and to decide what feels compelling, important, beautiful. And it’s not all in our heads.

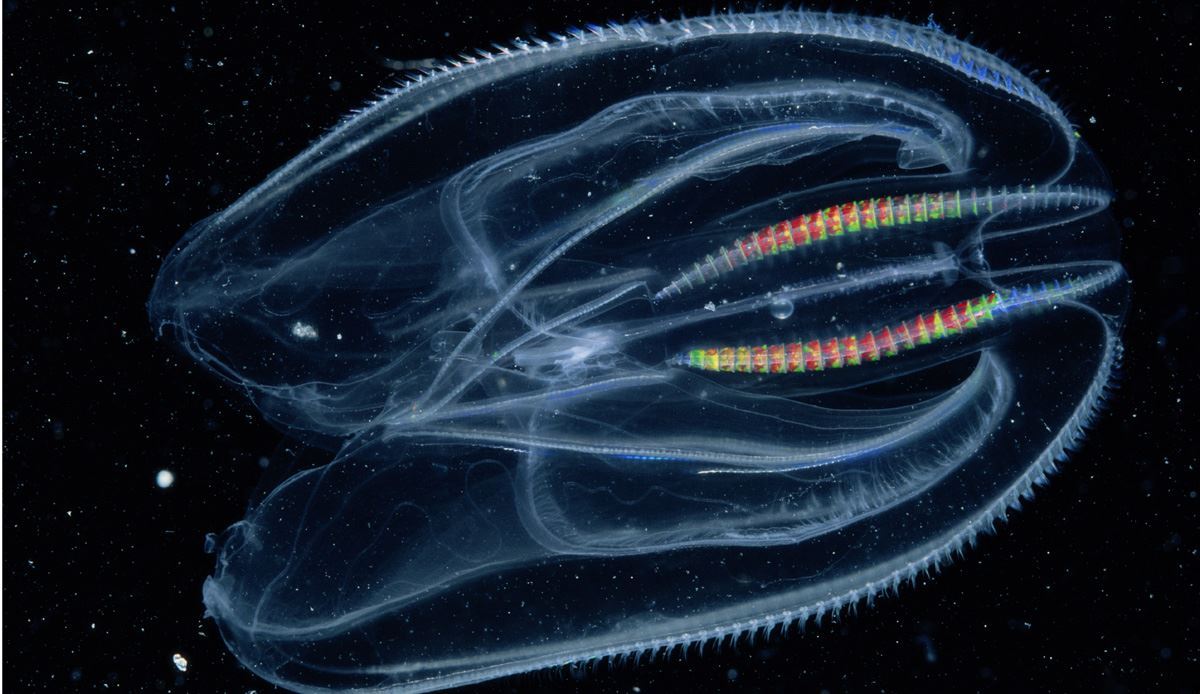

t’s fascinating to me how memory and associations work; this weirdly human cognitive process (or set of connective processes) seems to wire us for poetry, for art, for metaphor, analogy, and symbolism–for dreams and the surreal, and for curiosity and wonderment.

t’s fascinating to me how memory and associations work; this weirdly human cognitive process (or set of connective processes) seems to wire us for poetry, for art, for metaphor, analogy, and symbolism–for dreams and the surreal, and for curiosity and wonderment.