Earlier this week, I went to a neighboring city–Reading–to record a TV segment for the local station, BCTV, that hosts a program about poetry! The host and interviewer is poet Marilyn Klimcho of Berks Bards (a non-profit poetry group in Berks Co, PA). It was truly pleasant to read a few of my poems in a professional setting (studio), but the best part of the day was just chatting with Marilyn about poems, poets, and poetry. We began our conversation half an hour before the cameras rolled and continued it afterward, so the 25 minutes that were recorded seemed just to be part of a longer, casual discussion.

I appreciated that. I’m part of a long-running critique group, but it’s seldom that I get the opportunity to pick someone’s brain and share ideas, influences, and general enthusiasm about the art of poetry the way I did in grad school. Probably could work on getting more such discussion into my life.

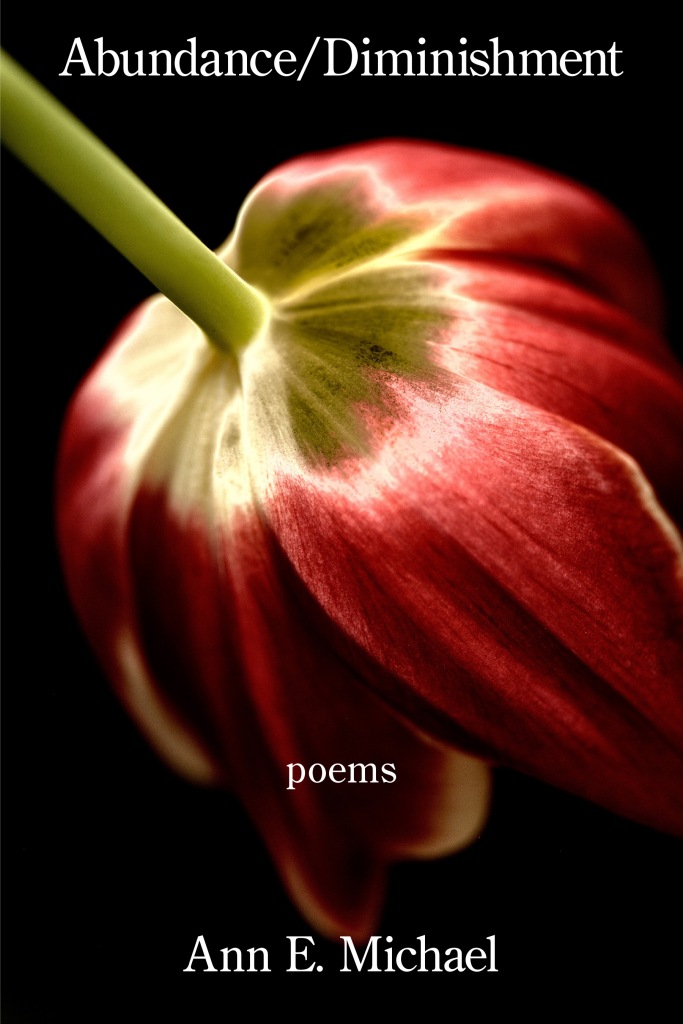

The “Poets Pause” segment will air in March and then reside on YouTube, so I will post that link at some point. It was kind of Marilyn to highlight The Red Queen Hypothesis and to give me a chance to mention my next collection, forthcoming from Kelsay Books later this year. Speaking of which, I do now have a photograph of its cover:

The photo is by Don Schroder, a friend who’s got a website full of lovely images from his numerous travels to the African continent as well as good shots of festivals of many kinds and floral beauties from arboretums and gardens. Go check it out!

The cernuous tulip seems appropriate to several themes I evoke in these poems–elegies and the sense of impending losses but also appreciation of beauty and brevity and life’s many colorations. Initially, I thought that I was using fewer of the animals, plants, weather and the “nature stuff” I tend to populate my poems with, because so many of the poems in Abundance/Diminishment are for or about humans. But…nope, just took another look through the manuscript in the final approval/editing process and realized that I cannot seem to leave the planet’s environment out of my work. I probably should have been a biologist, ecologist, or a science teacher instead of an instructor of English, but oh well.

Frankly, I love the simplicity of this cover, and I’m excited to have the book in print later this year…especially since it took me a decade to get The Red Queen Hypothesis into the world.

Among the perennials, weedy vines snake and coil: poison ivy, virginia creeper, bindweed, creeping charlie, nightshade, wintercreeper, wild cucumber. These plants make the process of keeping my perennial beds “clean” very challenging.

Among the perennials, weedy vines snake and coil: poison ivy, virginia creeper, bindweed, creeping charlie, nightshade, wintercreeper, wild cucumber. These plants make the process of keeping my perennial beds “clean” very challenging.