For my last National Poetry Month blog post, I respond to Grand Canyon, a mini-chapbook by Pennsylvania & Baltimore, MD poet Barbara DeCesare who, I confess, was a fellow student of mine when we were in grad school; and therefore I am tremendously biased about her work. But while bias enters into response to some degree, this post responds to the book, not to the poet. Well, okay–bit of both.

What’s different about this chapbook is 1) it is a long poem in 13 sections and 2) it is not available; I have a ‘self-published’ version personally photocopied and inscribed by the author. Therefore, I am reading what most of my readers do not have a chance to read. It’s kind of like finding a personal letter in a long-unopened drawer, and similar to the small chapbooks and photocopied zines of the late 1970s and 1980s. It is not easy to find those anymore, either.

DeCesare’s chapbook fits right in with my 1980s zines.

~

Grand Canyon is a long poem structured as a series of shorter poems and came to me with the following back story:

“A friend visited the Grand Canyon recently with his wife and two preteen daughters.

He told me about how terrified he was that someone was going to fall from the narrow path that descends in. Not just one of his kids, but anyone. It was more than he could bear.

So he left the trail and went back up alone. He didn’t want his fear to hold his family back.

It made me think about parenthood, empathy, fear, and love in my own life. About the balance between care and detachment, and the weird places where they overlap, like my friend’s experience.”

~

“He didn’t want his fear to hold his family back.” –This introduction felt oddly profound. I sat and thought about it for a long time before I turned to the first page of the poem itself.

Of which the first line goes: “An echo reminds you of your place in the world.”

Canyons, heights, fears. Echoes. Yes–as a person, especially as a person who has raised other people–I have felt those resonating. Often. The poem-pieces here are brief, poignant. They find me wrestling with my own worries, in my own life, which is not the poet’s life, nor her friend’s.

…I wonder/how long a mother can hold her child/before she needs that other hand on the railing.

The long poem, comprised of moments: short poems that feel so true I have to stop between each one, catch my breath, steady myself.

~

Thank you, my friend, for writing this poem for your friend–for your children–for yourself. For me.

(Someone ought to publish this poem/book.)

~

My initial responses to the poems herein vacillated between the intellectual and the…ear? Sound? I guess what I am trying to say is that a significant part of Doré Watson’s poetic craft employs sonic crushes of alliteration and internal near-rhyme, storms of assonant wordplay and sudden stops in syntax; just when the lyrical narrative seems almost to narrate a story, other pressures intervene. The feeling reminds me of times I cannot concentrate, when I’m full of either ideas and intentions, or fears and concerns.

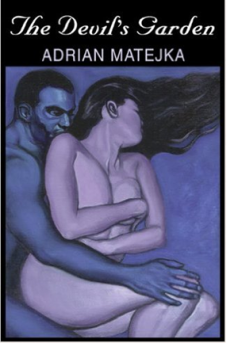

My initial responses to the poems herein vacillated between the intellectual and the…ear? Sound? I guess what I am trying to say is that a significant part of Doré Watson’s poetic craft employs sonic crushes of alliteration and internal near-rhyme, storms of assonant wordplay and sudden stops in syntax; just when the lyrical narrative seems almost to narrate a story, other pressures intervene. The feeling reminds me of times I cannot concentrate, when I’m full of either ideas and intentions, or fears and concerns. The language here is clear and fine, frequently musical–a trait I like very much. Matejka’s newer work engages with the ideas society and individuals have about tribes, groups, races, mixing, and this early collection establishes those themes. The voice here strikes me as youthful, newly-minted. But sure in its control of the rhythm and sound of a poem.

The language here is clear and fine, frequently musical–a trait I like very much. Matejka’s newer work engages with the ideas society and individuals have about tribes, groups, races, mixing, and this early collection establishes those themes. The voice here strikes me as youthful, newly-minted. But sure in its control of the rhythm and sound of a poem.