[note] *Hmmm. Somehow, I backposted this post. It was written June 23rd, post-solstice!

Actually, they’re wild black raspberries, someone informed me. They usually ripen around the end of June, and everything eats them–orioles, robins, catbirds, deer, possums, raccoons, possibly even foxes. Black bears, if they’re in the vicinity, though we haven’t seen one here.

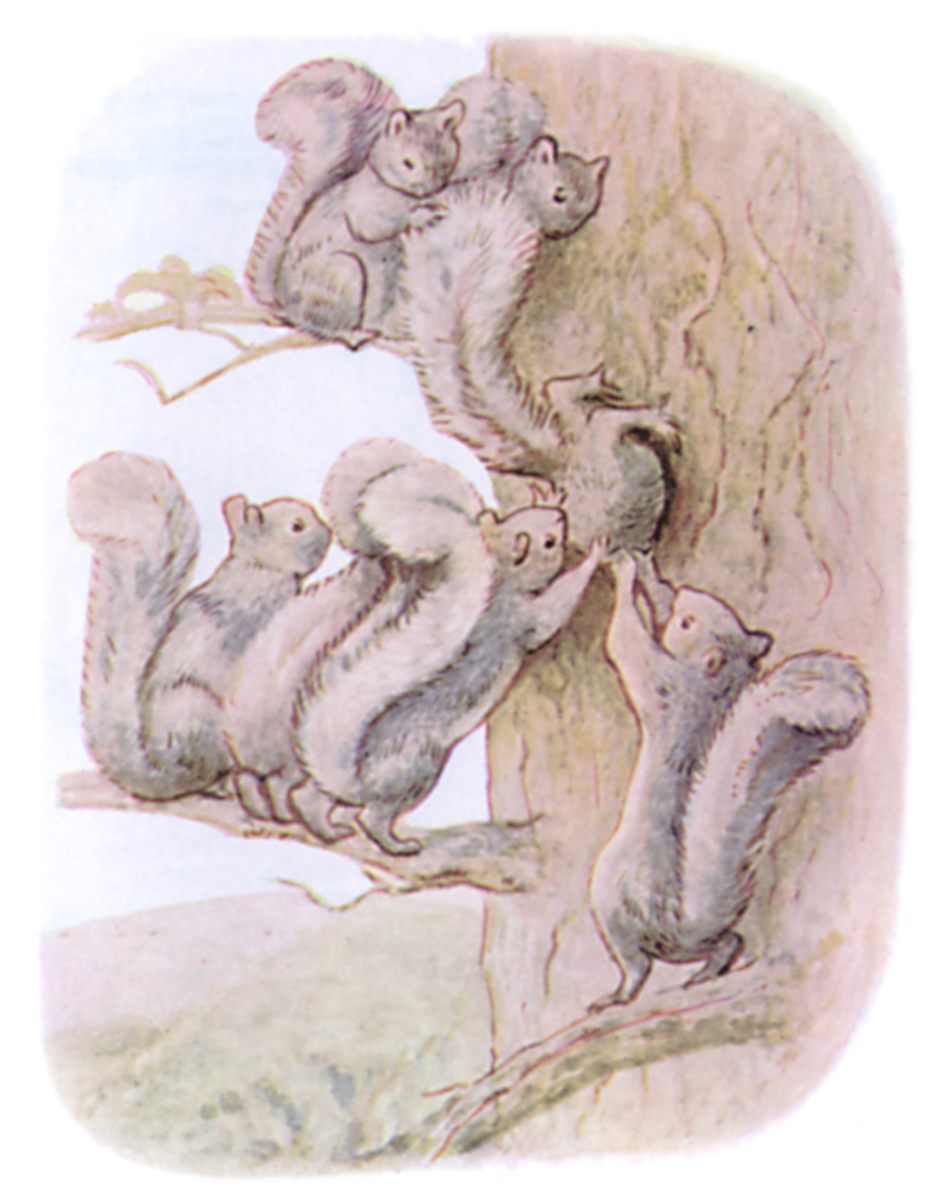

Humans enjoy eating them, too. Usually I don’t get more than a few for yogurt or ice cream toppings, but this year–a bonanza. Maybe the canes liked all that rain. Harvesting them is quite a task, because the canes are in the hedgerow thicket and twined about with poison ivy and cat’s-claw and other spiky and rashy flora, not to mention the thorns of the berry canes themselves. And harvesting comes as the hot, humid weather descends on this valley, making the effort a sweaty and uncomfortable one. I always think of farm workers, almost all of them immigrants, who get hired to do this sort of work–the vital work no one else wants to do. They deserve better pay and considerably more compassion than they generally receive. Half a quart of blackberries cost me half an hour of sweat, many scratches, and a swath of dermatitis; but, like Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail, I had bread and milk and blackberries, (for breakfast).

Current mood: harrowing. Aghast. These two poems, though I wrote them many years ago, seem apropos to the moment.

~

Like Thumbelina

Where there’s green foliage

so dense my eyes ache

I spend an hour in shade

snacking on blackberries

the birds haven’t found.

My head hurts from the agonies

of money. The cell phone rings.

Ferns and five-leaf vines

muffle street sounds,

a little colony of feathery mosses

sits under a tree-burl shelf.

I find a hole pressed snugly

against old roots and leaf-mulch.

Like Thumbelina,

I want to curl myself inside

a sassafras leaf, sleep

beneath a toadstool

undiscovered,

unmolested,

temporarily free.

~~

Thicket

Behold the thicket:

it is deep with brambles.

It is blackberries in July,

wineberries in August.

Move, and the thicket

impedes you, catches

your sleeve,

plucks you awake.

The bee is here. The spider.

The thicket is alive, and crawling.

Green with jewelweed to salve

rashes from the thicket’s

poison ivy. Green with prickly

horsenettle, coarse pokeberry,

the brilliant, twining nightshade:

thickets sweat poisons

as well as fruits.

I have brought you here to show

that you can never get through,

not unscathed, not without

brutality of some kind,

the saw, machete, knife.

This tangle no amount of patience

will ever undo—

it will overtake you,

grow into your hair,

invite warblers in to nest,

spiders to unfurl their orbs.

You must learn not to hate

before entering the thicket;

you must acknowledge all its ways

to understand its wild embrace.