Well, I have been writing. But less about the current wintry days than I expected, because of the online poetry seminar I’m taking.

One recent prompt in Anita Skeen‘s workshop involves employing phrases from a text and using those words, or images, as a start to a poem that would not encompass or even relate to the original topic. I’ve written work that does that; but more commonly I continue the topic in some way, most notably with my long-poem/chapbook manuscript The Librarian of Pyok Dong. And what I notice is that I tend to choose “unlovely” texts, articles or essays that are historical, scientific, or academic, rather than to use the words of poets or novelists. Why that is, I can’t say for sure; it may simply be due to my deep-rooted nerdiness. But I think of poets like Martha Silano, Rebecca Elson, Muriel Ruykeyser, and others who have created amazing work, beautiful poems, from newspaper articles, scientific papers, academic texts, encyclopedias–so I feel encouraged. The result, for me, however, is often an unlovely draft.

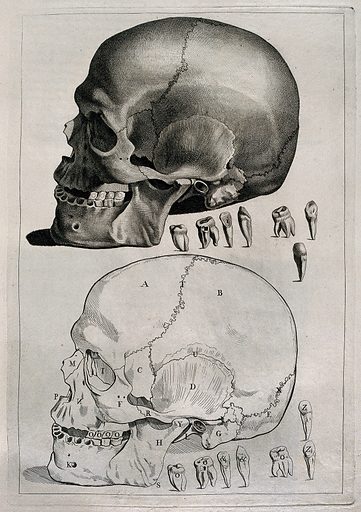

I have recently spent some time proofreading one of my brother’s papers that addresses the origins of some of the crania in Samuel George Morton’s collection, which resides at the Penn Museum in Philadelphia and is among the controversial holdings there of sacred/religious objects and human remains. The University has committed to “repatriating” such items in its collections that belong to indigenous peoples, for example, and to returning human bones to places of origin or to “respectful interment.” The challenge with Morton’s large collection is to ascertain where, in fact, these human beings came from. [Informational page is here.] My brother has been trying to track down the people, likely young Africans, who made up one set of about 55 skulls collected in Cuba around 1839-1840.

It’s a terrible history, of course. The Middle Passage, slavery, illness, misery, abandonment even in death. And it’s an academic paper, so the language–not to dismiss the author’s writing ability, since he’s keeping to the conventional style–does not lend itself to poetry.

Basically, I’ve given myself a difficult task. Yet we learn through difficulty, do we not? Often, too, the unlovely poems are those that deal with how rotten human beings can be, or illuminate the worst of times and offer us insight and information that we had not been taught, hidden horrors, trauma, all of the above. I have written many lovely poems about lovely things. The world, however, manages to be far more complicated than beautiful, a mixed bag of joys and miseries, and it seems to me that literature and art ought to reflect that fact sometimes.

What I’m posting below is a very rough draft, just to demonstrate how I begin a difficult poem, a poem based upon historical facts that I’m learning myself. It’s a completely different process from when I write from an image or observation of my own. For example, the “Librarian” poem, which is about 15 pages long, took me a couple of years and a visit to the United States Army Heritage and Education Center (USAHEC) at Carlisle Barracks, PA! First I pull some quotes, make a lot of notes, highlight images or place names that seem most resonant. Then I develop these into what I call “jottings” and fragments, and start setting them into an initial sequence–which I often change later.

Stanzas? Line breaks? Metaphors? Meter? All of that can wait; I like to work on structuring the narrative first when I try something in this vein, and I want to find images that might speak to a reader. So it is clear to me that this poem is not one I’ll have finished before the end of the 5-meetings-long workshop. Assuming I ever do finish it. Yes, poetry is hard work.

~

José Rodríguez y Cisneros, Havana Physician, Ships 55 Human Crania

to Samuel George Morton, Anatomist (1840)

A Cuban journalist writes that by 1915

“The Vedado of my childhood was a sea rock

over which the seagulls flew”

sandy, overgrown with Caleta sea grapes

the nesting-place of rats, iguanas

but once a cemetery for paupers and bozales,

the unbaptized, slaves, the suicides

abandoned on this coast as carrion

where turkey vultures and wild dogs

fed on corpses hastily interred

“el Pudridero” they called it—

the rotting place—

local people thought it cursed

for a more scientific-minded man, opportunity

to harvest skulls for anatomic pursuits.

Nameless, blameless nobodies

who were otherwise less than worthless:

the definition from a 19th century

Spanish dictionary:

“bozales. A Negro recently removed

from his [native] country—

metaphorical and vernacular,

one who is foolish or idiotic…

can be applied to wild horses.”

~~

*note~

“the Vedado Interment Site…originated as a sinkhole that came to be utilized as a mass grave…[the majority] of the Vedado Group likely consisted of enslaved people born in Africa during the early 19th century, most of whom died of infectious diseases soon after arriving in Cuba.” —John S. Michael