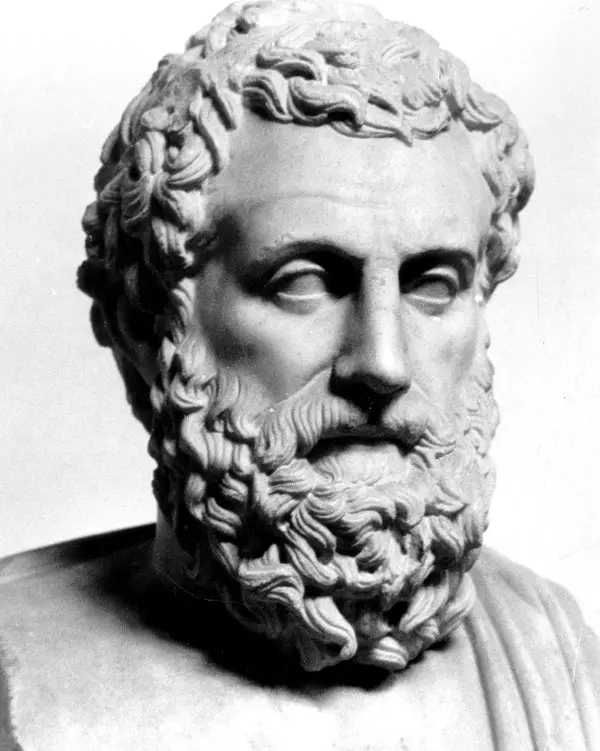

Holy pop-psychology, Batman! Introverts are asserting themselves all over the place! At least, you might think so based on current media trending. There was that insightful and rather humorous 2003 article called “The Care and Feeding of Your Introvert” in The Atlantic magazine. More recently, Susan Cain has brought us the book Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking. When popular culture embraces an idea, parodies and simplifications and misinterpretations spawn in the stream of cultural consciousness. Some of these are charming, such as Dr. Carmella’s Guide to Understanding the Introverted, with its hamster-ball analogy. Mostly, the chatter masks any actual usefulness of categorization. Categorization as a method of understanding has had its pros and cons going all the way back to that master of the process, Aristotle.

Batman is copyrighted by DC Comics

Recently, I’ve been participating in discussions, virtual and face-to-face, around the topic of introversion and extraversion as personality or character traits, and the value or lack of value of the categories as well as the definitions of these words. Popular culture, which perhaps ought to be called majority culture, as usual flattens and simplifies the concepts. “Introverts” are shy and quiet, “extraverts” are sociable and talkative.

Or not. The current psychological meaning of introvert is based on the work of Isabel Briggs Myers and her colleagues and means, broadly speaking, a person “predominantly concerned” with his or her interior thoughts or sensations and less concerned with “external things.” An extravert (sometimes confused with the non-psychological, more general term extrovert), by contrast–naturally–is more concerned with life’s “practical realities” and gains more gratification from what is outside the self.

A friend of mine recently blasted the Myers-Briggs type indicator assessment as being responsible for promoting stereotyped ideas of introverts and extraverts and claimed the assessment is worthless (she used an earthier term). I don’t agree that Myers-Briggs is worthless; like any assessment tool, however, it cannot provide anything more than a snapshot of a personality. It can provide useful insight when combined with careful observation, professional knowledge, and other methods of determining character and personality. Just because Myers-Briggs is probably the most-applied or most-trusted personality assessment tool in the world does not mean it is always accurate or can be interpreted by laypeople…or even by experts. Brief forms of the test online are just that: brief forms, less complex, and therefore–as human beings and the mind and consciousness and personality are exceedingly complex–considerably less reliable as to results.

Then there is the whole concept on which the test, and others like it, are based. Carl Jung posited the notion of two dichotomous pairs of cognitive functions operating in the human psyche, and the test is derived from his initial explorations concerning those dichotomies. Well, that works–if you are a dualist. Not all of us buy into the categorization program, and many skeptics suggest that the world is far more interesting than just pairing opposites can explain.

I love the idea of harmony the taoist symbol represents, but my sense of the universe’s fractal and relational saved-from-chaos-by-a-thread “reality” tells me things are not that simple. We simplify them to attempt understanding at the human level, but oversimplification leads to stereotypes and fallacies, outcasts and enemies. Introverts and extraverts can face off and talk about how different they are; but Jung and Myers would remind us that these “types” exist on a continuum, despite the dichotomous origin of the concepts. Some people test out right near the middle of the two; some are only partway between the extreme ends of their type. Furthermore, how one defines these terms makes a big difference in how the types are perceived…and people do change as we develop along our own continua.

My father was an early proponent of the Myers-Briggs assessment and has administered the test to me three times (when I was 17, about 26, and in my late 30s). As I matured, my introversion factor changed slightly. Of course, I could have told him that without the test! I had more time for daydreaming at 17, and fewer external responsibilities. By the time I was nearing 40, I had to deal with some significant external realities: my young children and all the practicalities of external life that child-raising entails. The other aspects the indicator assesses changed a bit less, but there was movement; human beings are not stone carvings, and even stone carvings wear down, break, and change.

My own definition of what it means to be an introvert is that I “recharge” best when I am alone or with another person who is quietly reading or walking or daydreaming alongside me. I do not like being lonely; loneliness can occur even when surrounded by society, however, and solitary hours aren’t necessarily accompanied by a sense of loneliness. After spending a day at work, talking with students and colleagues–activities I enjoy–I need to go up to my room and get out of my work clothes and unwind without immediately chatting about my day. Parties can be fun, but afterwards, I need to spend a little time by myself. Concerts and tourist-clogged beaches can overwhelm me, yet that doesn’t mean I find no joy in attending them. I just need to pad the experience with some quiet time before and afterwards. Some of my family members, though, feel drained when they are quiet for too long. They recharge by socializing, or by making and doing things (ah, those “practical realities”!).

I was considered shy as a child and adolescent, but few of my current friends would say that shyness is one of my most obvious characteristics. These things are matters of environment and perception, not merely of some implacable temperament. In fact, I have several friends who appear much “shyer” than I am but who are extraverts, because they feel a sense of increased energy after social interactions or going to concerts or cities, whereas I need to retire, book in hand, to my quiet chair for recuperation. Ask anyone who knows me and you’ll learn that I love to talk and can be quite gregarious. Sometimes. And after awhile, my need to transmit and receive sort of slows down. After that, I don’t need to have anyone attend to me, converse, or ask me if I need anything. I don’t need interaction anymore–I’m like a cellphone nestled in its charger.

Even a cellphone needs a few minutes when no one is talking. That doesn’t negate its role as a conduit for communication, does it? As any reader can tell from this blog, I am concerned with “interior” thoughts and sensations but speculate on and relate these thoughts to the wider world, which is also my main impetus for thinking these thoughts in the first place.