My local public library’s poetry section is on the sparse side. However, after renewing my card today, I felt determined to borrow a poetry book. I considered taking out one of Louise Glück’s collections, but I already own copies of the two on the library’s shelves (Wild Iris and Meadowlands). I chose Maxine Kumin’s 1992 book Looking for Luck instead. When I returned home, I learned that Glück has died (age 80). There will be time to return to her books and to seek out her most recent collection, which I have not read; but hers is a voice readers of poetry will miss.

One thing that her poems do is to face, without shying away from, sorrow or grief. They seldom offer sociably-conventional consolations. The consolation is in the spare beauty of her observation, her control of language. That is difficult to do. When I write from despair or deep grief, I find I want to bring some kind of–call it hope?–into the last few lines. I wonder whether I’ve a tendency to want to comfort; maybe my readers, maybe myself.

I haven’t gotten very far into the Kumin book yet, but it’s clear that this collection includes numerous poems featuring horses, one of Kumin’s lifelong joys (she and her husband raised quarterhorses in New Hampshire). Her poems have taken me back in time, so to speak, to when my daughter was learning to ride. I have had a sensible regard for horses’ size, prey instincts, teeth, and hooves from early childhood–not quite a fear of horses, but pretty close–so when my then-tiny nine-year-old expressed an unwavering and stubborn interest in riding lessons, I held off until persuaded to let her “just try it.” Of course she knew what she was interested in, and of course she loved riding, despite frustrations and beasts who didn’t want to cooperate and being pitched off and stepped on while I watched and encouraged and soothed, swallowing my fears for her safety.

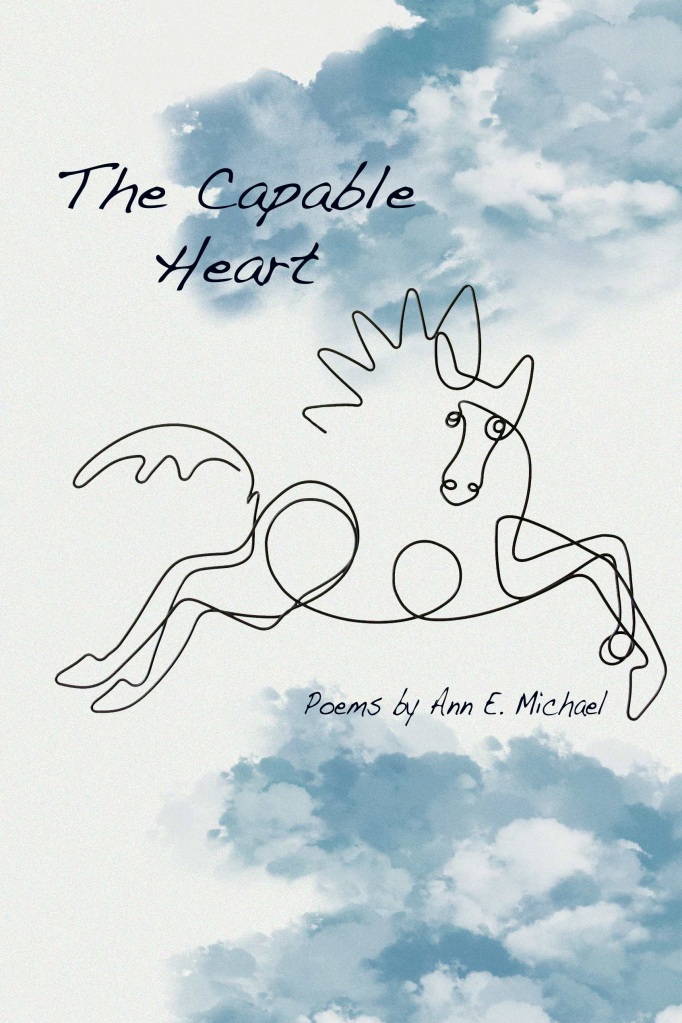

Equine grace, strength, personality did not quite win me over; I’ll never be much of a rider myself. But contending with horses and learning to love and commune with them was good for my child, and reading Kumin’s poems brings back how human animals can have relationships with other animals. I never quite got over horses being an “Other” for me, but observing how my daughter loved being with them inspired me to write quite a few poems of my own [see my chapbook The Capable Heart]. Reading Kumin’s work takes me to a familiar and important place in my own life.