Last year at this time, I had covid and was languishing in bed, unable to tend to the garden. A regional drought meant I really should have been watering the new plants; and it also kept the weeds firmly rooted, fighting for dominance in the vegetable patch. This year, I timed a trip to New Mexico just when I ought to have been harvesting spinach and planting out tomatoes, beans, and squash. Oops. And then it rained buckets the whole time I was away (much-needed rain, but…). Therefore, the garden situation was not ideal. But garden situations seldom are ideal because Nature does its own thing regardless of my plans.

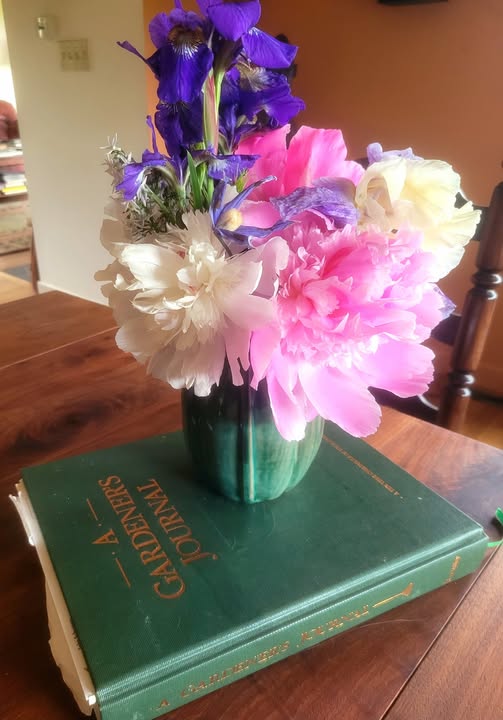

At any rate, eastern Pennsylvania finally moderated its weather enough that I got the weeds and the seeds and transplants more or less under control this past week–“control” being a general term subject to, well, Nature. The peonies bloomed gorgeously on schedule, as did the nefarious multiflora roses and Russian olives that plague the hedgerow. The catbirds and Eastern kingbirds are back; the robins’ first brood has hatched; the orioles are insistent in the walnut trees and brilliant in the garden, chasing the barn swallows. I’m not doing much writing, though I drafted one or two beginnings of poems. Outdoors takes precedence–not that I can’t write out of doors, I often do so. But poems can wait in a way the garden cannot.

And, speaking of poems (and Pennsylvania), I returned from my trip to find this Keystone Poetry anthology awaiting: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09990-3.html–the followup to 2005’s Common Wealth anthology, also edited by Marjorie Maddox and Jerry Wemple.

The new anthology, 20 years after the initial one, has poems by about 180 poets–yes, I am one of them–covering the corners and the center of the Keystone State. I like it even better than the first collection, and it is clear the editors learned much from the experience of curating poems and creating a cohesive “experience” of the regions. Granted, since I know both of the editors personally and appreciate their poetry and their visions, I may be biased. But that’s okay. Objectively, I truly get how huge an undertaking this was and how well it has turned out. For educators, there is a section at the close of the anthology full of suggestions for reading, writing critically, and writing creatively based on this anthology, and even in comparison with the previous one. As both editors are college professors who teach creative writing and critical writing, these appendices are well-thought out and worthwhile.

I miss the aridity of New Mexico, which seems to benefit my overall health. And I miss my daughter immensely. But springtime in eastern PA has many compensations, not the least of which are blooming even as I write.