Ariel Dawson, 1959-2013

I recently learned that a friend who was hugely significant in my life once, but with whom I had lost touch for 15 years, no longer walks the same earth that I do; in fact, Ariel Dawson died in 2013, unbeknownst to me.

Ariel Verlaine Dawson

It is hard to lose friends, but losing the friends of one’s youth–those intense, passionate friendships that teach human beings how to navigate the world of human relationships–that loss cuts in a different way. For Ariel is perhaps the reason I am a writer. No–I would have become a writer. She is the reason I decided it was possible to be a poet. She amazed me with her vocabulary, her insights, her evaluative reading, her positively voracious and precocious reading, her charm, her gentle goofiness, her forthrightness, her neurosis; she seemed to fear nothing (but that wasn’t true); she had published poetry in real journals before she was 17 years old; she read Rilke and Yeats; had affairs with well-known poets; spent years fathoming Jung. In 1994, she wrote an opinion piece for what is now AWP’s Writer’s Chronicle responding indignantly to Dana Gioia’s article “Can Poetry Matter?”–a piece that started quite a dust-up among defenders of what has been termed “new formalism.”

Ariel had always been the sort of person who chose to disappear and then to reappear, to my joy, months or years later to take up the friendship without pause–and often without explanation for her absence. She had her reasons, and I respected that; but I missed her.

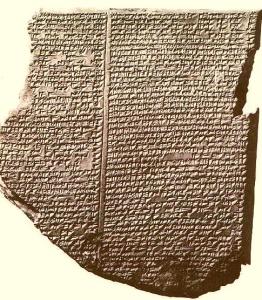

Ariel, 1977 or 78

~

In the early 1980s, my (also late) friend David Dunn and I were publishing chapbooks under the small-press name LiMbo bar&grill Books. We approached Ariel for our second-ever chapbook: Poems for the Kazan Astrologer. She was, at the time, teaching creative writing at Old Dominion University. We were very happy with the outcome, but we had no good method of distributing the books. I may still have a box of 25 or so of these books somewhere in my attic.

Then Ariel became more intensely interested in Jungian psychology, though it had long been a passion of hers.

In subsequent years, she wrote less and less poetry and stopped submitting her work for publication. The response to her Writer’s Chronicle opinion was, I think, a bit shocking to her, though I know she stood by her opinion. She just decided, perhaps, that she felt more at home in the world of Jung and his followers.

During the past decade I have often tried tracking her down, imagining the internet would find her. My job at the college has made me a rather adept online researcher, but all that ever showed up was a listing for her psychotherapy practice in New York City. The number was incorrect.

Then, my father became very ill and other issues crowded my mind. Searching for a friend who clearly wanted to remain anonymous in an electronic era was not a priority.

Besides, I always assumed that Ariel would suddenly re-emerge, call me–my phone number remains the same as it was last time I saw her–and mention she was going to be in the area, and could she stop by? That’s how it had been before. And I’d be thrilled to see her, and we’d talk about poetry and art, and politics and pets, cheese, philosophy, psychology, parents, wine…

I assumed incorrectly. That’s what happens with assumptions. Just this past week, when I finally found myself with some spare time, I tried an internet search again. And found her “electronic obit” online, and the fact that she’d died in February of 2013.

~

I have no words to express how this information feels to me.

And also–

~

Arthur Cadieux, 1943-2015

Arthur Cadieux in 1978, a photo taken by Jim Terkeurst.

Arthur 2011, Eastport, Main

Arthur in 2015. Photo Elizabeth Ostrander.

~

Arthur Cadieux was my art teacher at Thomas Jefferson College in the late 1970s. He and his wife, Helene, were exceptionally kind to young adults who had an interest in art and in observing the world around them. We had dinner at their house in Michigan and at their loft apartment in New York City. Years later, after Helene’s tragically early death, and after Arthur had moved back to Maine, he let me stay at their cottage on Leighton Point (he lived in a smaller house in town) so that I could have a personal “writing retreat.” He deeply understood the creative person’s need for reflection, evaluation, thought, imagination, boredom, and occasional moments of lively talk. The universe needs people like Arthur Cadieux, talented and generous, who are constantly pushing their own boundaries. Many of us who benefited from his friendship will miss him. Arthur’s paintings can be found at his website, arthurcadieux.org.

~

May they be free from suffering and causes of suffering.

May they never be separated from the happiness that is free from suffering.