I have blogged about the Myers-Briggs personality inventory–a tool that may or may not be useful to psychologists, depending on whom you talk to. Because my father used the inventory in his studies of people in groups, he “experimented” with his family, administering the inventory to the five of us. I was 17 years old the first time I took the survey; my type was INFP (introvert, intuitive, feeling, perceptive), heavy on the I and the F. Has that “type” changed over the years? The “brief” version of the test now shows me moving in the last category, still P but slightly more toward J (judgment). That makes sense, as I have had to learn how to keep myself more organized and ready for difficult decisions. After all, I am a grownup now.

The personality type does not indicate, however, what sort of thinker a person is. Certain types may tend to be more “logical” in their approach to problem-solving, and others tending toward the organized or the intuitive, but what do we mean by those terms? For starters, logical. Does that mean one employs rhetoric? That one thinks through every possibility, checking for fallacies or potential outcomes? Or does it mean a person simply has enough metacognition to wait half a second before making a decision?

Furthermore, if personality type can change over time (I’m not sure the evidence convinces me that it can), can a person’s thinking style change over time? Barring, I suppose, drastic challenges to the mind and brain such as stroke, multiple concussion damage, PTSD, chemical substance abuse, or dementia, are we so hard-wired or acculturated in our thinking that we cannot develop new patterns?

There are many studies on such hypotheses; the evidence, interpretations, and conclusions often conflict. Finally, we resort to anecdote. Our stories illustrate our thinking and describe which questions we feel the need to ask.

~ A Story ~

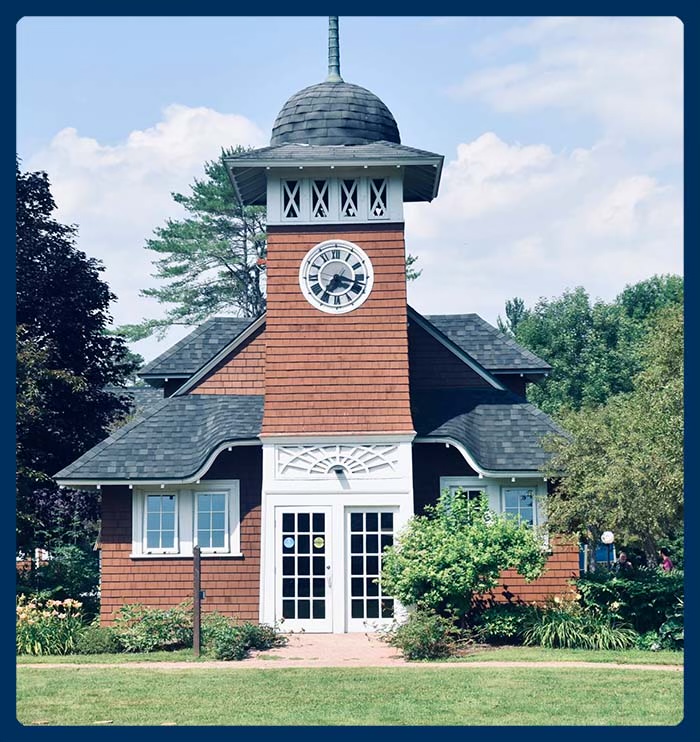

This year, I did the previously-unthinkable: I attended a high school reunion.

We were the Class of 1976, and because our city was directly across the Delaware River from Philadelphia–the Cradle of Liberty! The home of the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall!–the bicentennial year made us somehow special.

Not much else made us special. Our town was a blue-collar suburb of Philadelphia, a place people drove through to get to the real city across the river, a place people drove through to get from Pennsylvania to the shore towns. Our athletics were strong, our school was integrated (about 10% African-American), people had large families and few scholastic ambitions. Drug use was common among the student population, mostly pills and pot. There were almost 600 students in the class I graduated with, although I was not in attendance for the senior year–that is a different story.

But, my friend Sandy says, “We were scrappy.” She left town for college and medical school, became a doctor, loves her work in an urban area. “No one expected much of us, so we had to do for ourselves,” she adds, “And look where we are! The people here at the reunion made lives for themselves because they didn’t give up.”

It is true that our town did not offer us much in the way of privilege or entitlement, and yet many of us developed a philosophy that kept us at work in the world and alive to its challenges. The majority of the graduates stayed in the Delaware Valley region, but a large minority ventured further. Many of these folks did not head to college immediately, but pursued higher education later on in their lives; many entered military service and received college-level or specialized training education through the armed forces.

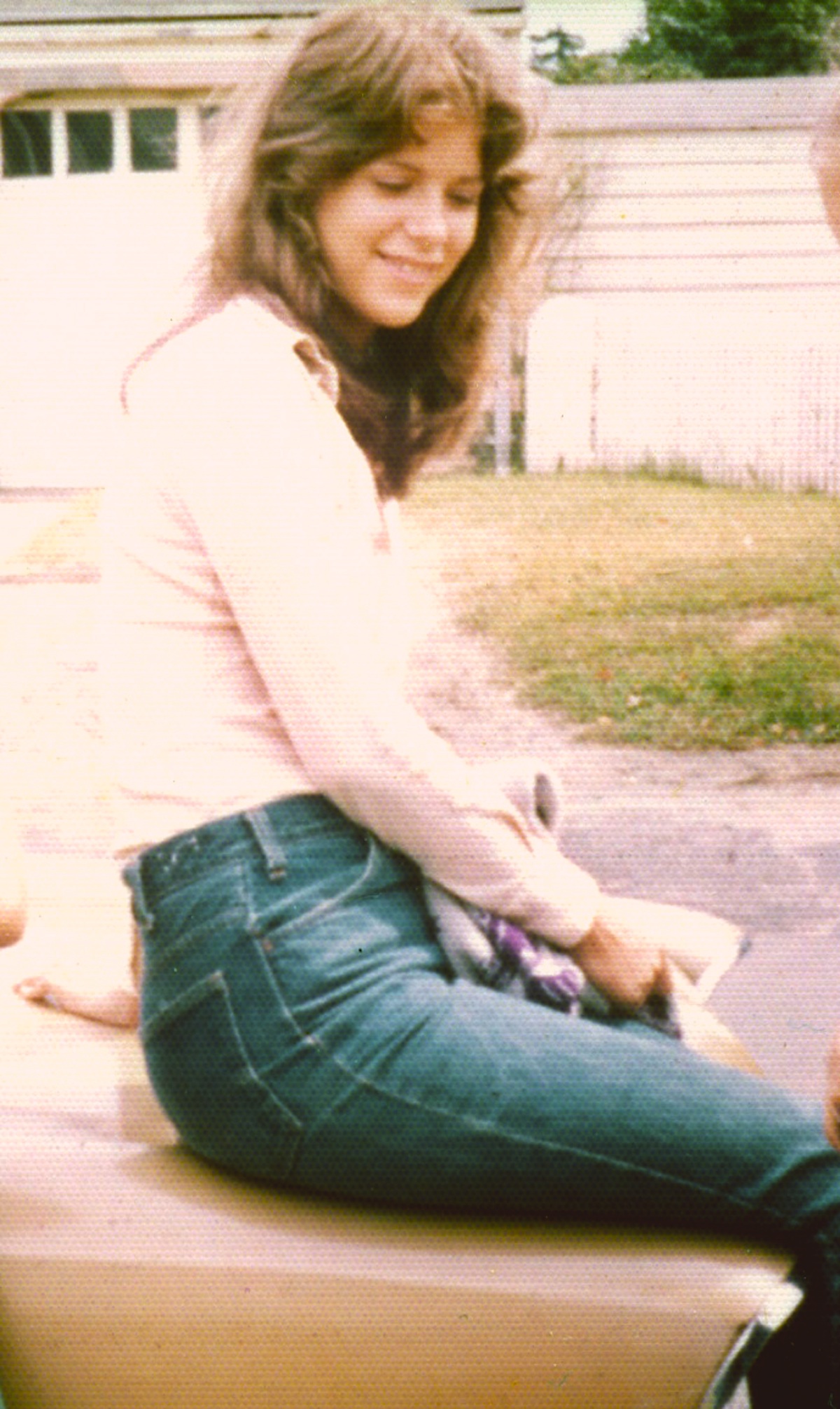

Does this young woman look logical to you?

I wandered far from the area mentally, emotionally, and physically; but then, I was always an outlier. One friend at the reunion told me that she considered me “a rebel,” a label that astonishes me. I thought of myself as a daydreamer and shy nonconformist, not as a rebel! Another friend thanked me for “always being the logical one” who kept her out of serious trouble. It surprises me to think of my teenage self as philosophical and logical. When one considers the challenges of being an adolescent girl in the USA, however, maybe I was more logical than most.

I find that difficult to believe, but I am willing to ponder it for awhile, adjusting my memories to what my long-ago friends recall and endeavoring a kind of synthesis between the two.

~

The story is inevitably partial, incomplete, possibly ambiguous. Has my thinking changed during the past 40 years? Have my values been challenged so deeply they have morphed significantly? Have I developed a different personality profile type? Are such radical changes even possible among human beings, despite the many transformation stories we read about and hear in our media and promote through our mythologies?

How would I evaluate such alterations even if they had occurred; and who else besides me could do a reasonable assessment of such intimate aspects of my personal, shall we say, consciousness? Friends who have not seen me in 40 years? A psychiatrist? My parents? A philosopher? It seems one would have to create one’s own personal mythology, which–no doubt–many of us do just to get by.

I have so many questions about the human experience. But now I am back in the classroom, visiting among the young for a semester…and who can tell where they will find themselves forty years from now? I hope they will make lives for themselves, and not give up.