so, I did what I set out to do: I exercised the necessary discipline to draft a poem a day during National Poetry Month, and I pushed against my “comfort zone” by publicly posting those drafts as they came to me. Usually I do not share my initial drafts with anyone other than fellow writers in my writer’s group or a few poets with whom I correspond. This was an interesting experiment on the personal level, therefore, a sort of forced extroversion as well as effort in productivity. I now have 30 new drafts to reflect upon, revise, or ignore.

It has been years since I came up with that much work in four weeks’ time. For the last decade or so, my average has been closer to six or seven poems a month. And I would not have posted any of them as they “hatched.” I would have waited until I spent some time with them and figured out how best to say what they seemed to want to say.

That’s not an unwise approach in general; I see nothing wrong with letting poems stew awhile. And quite a few would have ended up in the “dead poems” folder. Nevertheless, trying something innovative tends to prove valuable. The takeaway is that I am glad I finally managed the NaPoWriMo challenge. A few of the poem drafts you may have read here stand a chance of evolving into better poems. Maybe some will end up in a collection (years down the road). That result feels good.

The takeaway is also the realization that I no longer worry about how others judge my poems, the way I did when I was starting out and discouraged about having my stuff rejected by magazines. Not because there’s less at stake–indeed, I feel as invested in my writing as I ever was. The difference comes with the kind of investment, the ambition to write something meaningful or beautiful, and not viewing the poems as results waiting to be determined as valuable by someone more authoritative.

I’m 60 years old and well-educated in poetic craft, style, purpose, analysis. I’ve been writing poetry for over four decades. At this point in my life, that’s authority enough.

~

Self in the World

Goose stands sentry in the dew-strewn meadow.

Blackbird browses dry grasses woven along embankment,

emerges, slim stems clenched in its beak.

Under the footbridge, polliwogs gather,

backing into its shade–hawk overhead,

bluejay screaming territory! the crows respond–

Sun halos the water-strider’s shadow,

making a cluster of coronas on submerged stone

where wood frogs squeak and leap into stream current

surrounded by bedstraw, henbit, dandelion,

Amur honeysuckle, garlic mustard, stiltgrass,

invaders all. Except the frogs, who found the stream–

itself new to the landscape, gouged here in the 70s.

What do I notice, then? That some of the living adapt?

What do I make of myself in this world?

~

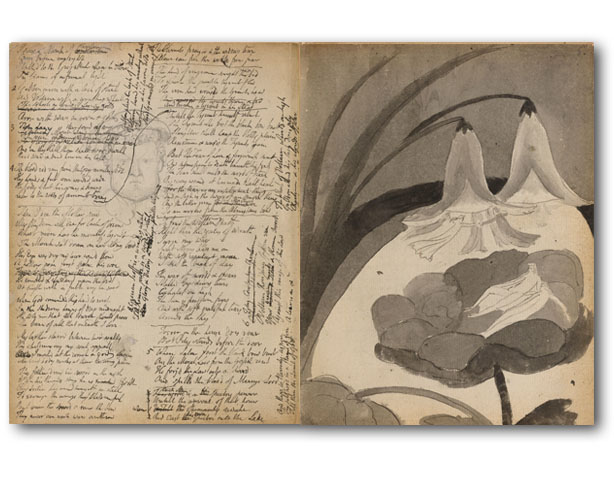

Photo by Brett Sayles on Pexels.com

~

Finally, to close the month of April, here is a lovely tribute to Mary Oliver by her friend and fellow poet, Lisa Starr.

Thank you for reading, and for the support of readers and poets this month.

I am going to go out on a limb here and make a blanket statement: Revision should be every writer’s middle name.

I am going to go out on a limb here and make a blanket statement: Revision should be every writer’s middle name.