The weather warmed and got windy, and that bodes reasonably well for garden prepping even if the last frost date is still almost a month away. I got digging, sowed more spinach and carrots, cheered on the lettuce sprouts, and–with some help from Best Beloved–pried most of the winter weeds out of the veg patch and set up a raised bed or two.

While I was out there pulling creeping charlie and clover and reviewing my garden plan for this year, it occurred to me that my process in gardening parallels my process in writing. My approach to each has similarities, probably due to my temperament though perhaps due to the way I go about problem solving. The process is part habituation or practice and part experiment, with failure posing challenges I investigate with inquiry, curiosity–rather than ongoing frustration. And sometimes, I just give up and move on without a need to succeed for the sake of winning.

I have no need to develop a new variety of green bean nor to nurture the prize-winning cucumber or dahlia. My yard looks more lived-in than landscaped; on occasion, we’ve managed to really spruce the place up, but it never stays that way for long. I admire gorgeous, showy gardens but am just as happy to have to crawl under a tree to find spring beauties, mayapples, efts, rabbit nests, mushrooms. My perennials and my veg patch grow from years of experimentation: half-price columbines that looked as though they might never recover, clumps of irises from friends’ gardens, heirloom varieties I start from seed. The failures are many, but I learn from them. Mostly I learn what won’t grow here without special tending I haven’t energy to expend, or I learn which things deer, rabbits, groundhogs, and squirrels eat and decide how or whether to balance my yearning for food or flora with the creatures that live here and the weather I can’t control. There are a few things I’ve learned to grow reliably and with confidence–ah, the standbys! But the others are so interesting, I keep trying.

Writing poems? Kind of similar. After so many years of working on free-verse lyrical narrative, I feel confident in my control of those poems and can usually tell when they’re not operating the way I want them to. Then I wait and revise and rethink, but there’s a familiarity to the process. Whereas I am far less confident with sonnets–nonetheless, sometimes a poem really works best in a form like that. So I know I have to expend more energy on it. Other times I find myself needing to experiment. I try mimicking another poem, tearing apart my line breaks, or revising in a form I barely know. I play with puns or alliteration, alter punctuation to stir up the rhythm or surprise the reader (or myself). Breaking my habitual approach to starting or revising a poem leads to curious results, sometimes intriguing ones.

But, like my garden ambitions, my writing ambitions exist more as a means to learn and experiment. I do not set out to produce the decade’s best poem or to develop a unique style or form that academics will admire and study. (I just made myself chuckle.) Heck, most of my work has not yet seen print–and with good reason. Not every rose is an RHS Garden Merit award winner.

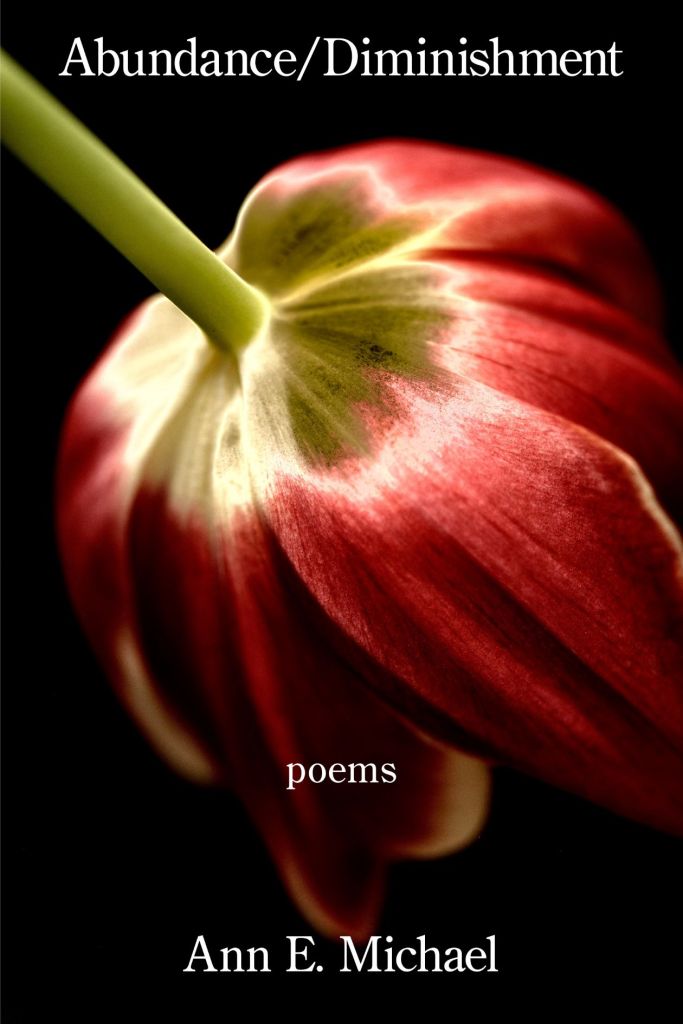

For now, here’s a poem I wrote over a decade ago, one that will be appearing in a forthcoming chapbook. More on that when I know more myself.

~

STILL LIFE WITH WOMAN

Loose sleeve envelopes her brown hand

which rests upon an apple or a secret

cupped beneath; only the stem shows,

fruit’s oblate body intimated by

the solidity of her skin against

the table’s plane.

This is a moment undiscovered,

a painting by Vermeer—

blue, white, quince-yellow, poised—

her palpably-dimpled wrist sloping

toward the precise, thumbnail shadows of

her relaxed fingers. We know

blood imperceptibly alters the shape of her veins

every second her heart beats, we know her womb

continues its cyclical pulse, that she inhales

and exhales, a living form, yet—

still: an inclination of the white, loose sleeve,

half an eye open, she covers some promise.

This is only one second before

surprise or boredom, a miniature:

one of those moments we find ourselves

in parity with every other thing,

equal in being to quince, fan, mirror,

that pitcher of water on the sideboard,

that window, full of light.

~