I’m embarrassed to note that the name of Proust evokes hilarity in my two (adult) children, since they immediately think of the Monty Python skit (see it here). Needless to say, neither of them has read Proust; but at least they have some familiarity with the famous writer, so I’m not a total failure as an educational model for my kids.

I read the novel(s) at age 19 or 20 and was entranced. Probably that indicates a kind of romantic nerdiness on my part as well as a love of words, of art and music, evocative sentences, descriptive prose, complex emotional situations, history, and confusion about the world of adults I was at that time entering. That I stuck it out through all seven volumes of the Scott Moncrieff translation says something about my persistence with literature and the beauty of that translation. [The Public Domain Review has a nice overview essay on Moncrieff here.] In the decades that followed, I kept meaning to re-read In Search of Lost Time; but it’s quite a commitment and, let’s face it, that is the sort of plan one tends to postpone.

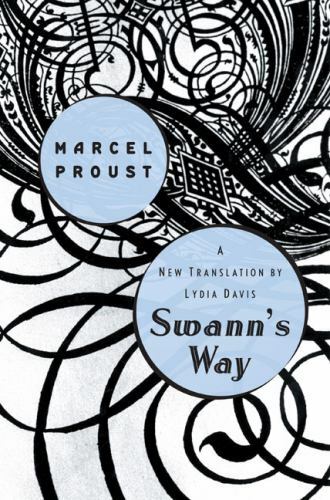

But I began the task this summer with the Lydia Davis translation of Swann’s Way, though I may move on with the Moncrieff editions if that’s what I can find at the library. (Somewhere in my attic is the three-volume Mitchell edition, but I started that years ago and found I didn’t like his approach.) I suppose a first-time reader might want to experience the books all through the same translator, but even the Moncrieff doesn’t succeed in that since he died before he got to Time Regained. The new Penguin series, for example, has a different translator for each book.

Ah, the difficulties of translation. If only I could read French!

During the past decade, I have done a smattering of re-reading novels (and poetry collections) that I first read in my late teens or very early 20s: Tolstoy, Woolf, Dostoevsky, Dickens, Blake, Atwood, LeGuin, among others. It’s always interesting to re-read a book that I haven’t read in decades because, although the book has not changed, this reader has, to some extent at least. Fewer allusions and implications go over my head, for one thing. The motivations of mature characters make more sense now, and the yearnings and errors of youthful characters, while sentimental and familiar, seem distant; also, I have a better sense of the historical eras in which these novels were set or written. As a teenage girl in the USA in the late 1970s I had very little background in the social strata of fin de siècle France or of Russia during the Napoleonic Wars, or even of Victorian Britain, yet the authors swept me up in the petty striving and the political aspects of their worlds…and the difficulties involved in surmounting them, achieving them, or living outside of society’s expectations.

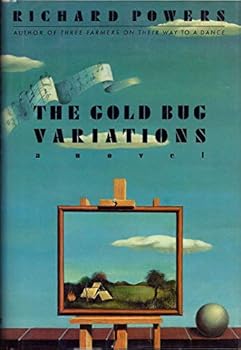

For all that I may be the wiser now, and can pick up more of the irony and humor, and more of the ‘adult themes’ (for example, until I was 17 or so I knew absolutely nothing about homosexuality), it is still the beauty of the prose and the rhythmic sweep of sentences and paragraphs that get me wrapped up in a book like this one. Besides, I love art and artists, architecture and music, and evocative descriptions of landscapes and gardens just as much now as I did then–possibly even more. Proust introduced me to so much when I was first reading these novels. Because of him, I read Racine, and Zola, and art criticism of the early 19th century, and looked at Impressionist painting in a new way, and recalled to mind the one trip I have ever taken to France (three years earlier, at age 16) as his novels described the Champs-Elysées, the Louvre, Versailles, the streets and parks of Paris’ arrondissements, and the villages in the countryside through which we had driven in a rented Opel.

Now, those recollections of France are dim. And the world has changed in 50 years. Proust knew: if I were to return, I would not be likely to reclaim my past–possibly not even remember it. France would be new to me, which is an idea I rather like. Possibly I’ll go back; in the meantime, I will relish the remembrance of reading what I have read in the past.