Creative writers are often asked where they get their ideas from. In my own case, the answer to that varies a great deal. Sometimes ideas arise from personal experience, of course, but one’s life offers only so much material if you are a relatively staid person like me. Topics for poems can arise from recent headlines or from histories, written or oral; from conversations overheard in a grocery line; from stories other people tell me; from folk tales; from science books; from dreams; from works of art, and numerous other sources. It’s this wide array of possibilities that make the concept of the creative-writing prompt so popular. A quick Google search for “creative writing prompts” offered well over 20+ pages of entries, in several languages.

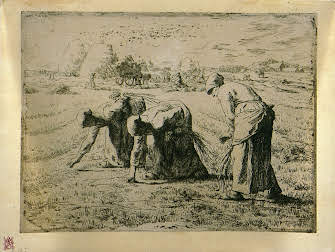

I have written pieces based upon prompts, especially when in a workshop or class, or when I feel rather tapped out of my own imaginative source material. I’m especially fond of writing that stems from viewing or experiencing a work of art–sculpture, painting, musical composition, dance, installation art (ekphrastic poems). Generally speaking, though, that’s not from whence my poems originate.

I can’t really say why I feel an urge to put down in writing specific reflections about something that’s caught my attention–or even what sort of experience evokes my response. Maybe I feel intrigued by an image, a detail, or an ambiguity–a question arises in my mind that I tussle with for awhile. Then, I may compose a draft and let it sit. Two days. Two years. Longer. Lately I’ve been revising some old poems and have realized I no longer recall what their incipience was. Which can be a good thing, because I am no longer wedded to the “reason” I wrote them and can instead consider whether they can be crafted into decent poems.

I am also working on a manuscript that I let sit for at least six years. An idea got into my mind after reading Robert Burton’s 17th-century book on depression, The Anatomy of Melancholy, quite some time ago (2017, perhaps?). I took a stab at writing what seemed to be evolving into a historical fiction story, which is not my usual approach (I have zero practice at plot and dialogue). Then, I stopped. As one does. But the topic lodged in me somewhere, I suppose, and early this year I returned to it. What if, I wondered, the draft could be restructured into a series of prose poems? There might be a sort of hybrid novella-poem in the earlier draft.

That’s more or less what I’m developing, at least for now, and we’ll see what if anything emerges. It’s keeping me interested, which I like, and the experiment feels fresh compared with “writing what I know,” or writing “how” I know. Because yes, of course we ought to write what we know; but we also know about human beings, and we have imaginations, and anything is possible.