Driving the road that clings to the south side of our hill I notice the round bright moon over newly-gleaned cornfields and find myself thinking about the last essay in Margaret Atwood‘s book Negotiating with the Dead. I finished reading the book some days back, but the title essay worries at me somehow; I can’t let it go. Maybe it is because I perceive connections between her ideas on the ontology of story-making and Boyd’s evolutionary premise for narrative, or between conscious mind and story-making arising from the cthonic, the deeps, the under-earth “hells” to which our myth-makers and shamans, goddesses, musicians, poets and heroes journeyed in order to bring back–if nothing else–the story of the trek and the resulting wisdom. Maybe it is because “negotiating” with the dead raises the problem of consciousness in peculiar and challenging ways as well as the problem of communicating with people of the past and of the future. Or maybe because of that bogeyman that awaits us all: Death.

When I was quite a young child, age seven or perhaps earlier, I was seized with an insomnia-inducing fear of death that kept me in agonies as soon as darkness fell. I wonder if that had anything to do with my later need to “be a writer.”

Atwood suggests that all writers truck with the dead. We read the work of our ancestors-in-the-craft; they are often our first teachers. That important aspect of craft so many of us struggle to attain–the ever-illusive quality of “voice”–is what we notice in many of our beloved writers. Voice, perfect example of metonymy. It stands in for the departed body, the dispersed consciousness.

Here is Atwood holding forth at a dinner party of fellow writers:

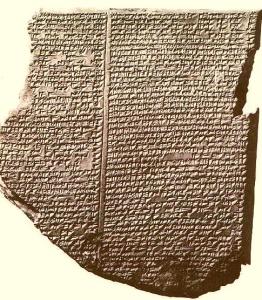

Gilgamesh was the first writer…He wants the secret of life and death, he goes through hell, he comes back, but he hasn’t got immortality, all he’s got is two stories–the one about his trip, and the other, extra one about the flood. So the only thing he really brings back with him is a couple of stories…and then he writes the whole thing down on a stone.

She adds that going “into the narrative process–is a dark road. The poets know this too.” So inspiration is not so much a clearing in the clouds but a kind of rappelling into a cave. At any rate, darkness, even with a full moon to light the road, seems as likely as a bolt of lightning to produce emotionally-resonant work. Maybe more so, because it’s harder work and more ambiguous (Lord knows, writing is both of those!). Darkness requires more interpretation. The audience has to listen, not simply see; the darker path gets traversed by both writer and reader.

Atwood also makes note of the threshold concept, that edge or invisible boundary line between the realms, any pair of realms. Life/death, yin/yang, heaven/earth, day/night. The one who seeks knowledge or magic or treasure (or lost love, viz Orpheus) at some point crosses the threshold, and then nothing is certain. He or she may not be able to return, for example. Edges are the interesting places, where all manner of things mesh and overlap–good spots for inspiration even if one opts not to take the stairway to the underworld; but they also pose danger. We humans, with our need for communities, invent parallel communities for our dead, not just physical cemeteries but supernatural abodes, and create all manner of “rules and procedures…for ensuring that the dead stay in their place and the living in theirs, and that communication between the two spheres will take place only when we want it to,” says Atwood.

I wonder if that is one reason I felt so unsettled by the idea of death when I was seven. I did not personally know anyone who had died (yet), but I knew the stories; certainly, I’d been taught about Jesus, though I was told he had defeated death. So why the early-onset angst? Did I fear that edge between the realms, being too inexperienced either to navigate it or to allow communication on my own terms? And maybe the fear is precisely what has led me to my ongoing inquiries into philosophy, consciousness, art, and mind.

Or was I precociously aware that I would have to venture into the darkness, into the coffin-holes and the caves and the seas’ depths, if I wanted to come back with a story to tell?