The semester is over, and the juncos have returned to my back yard. One thing I have trouble assessing after teaching my class is whether the students have made any inroads into learning the difference between a fact and an opinion, and argument and a disagreement, an interpretation and an analysis. But a response can be any of these things.

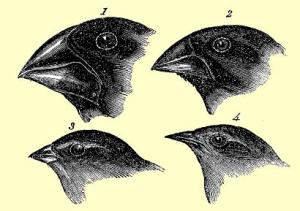

Thanks to wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons

Recently I have been entertained by Rebecca Solnit’s responses (as opinion). She’s made a bit of an earnest-minded internet buzz with her brief essay concerning Esquire magazine’s “80 Books All Men Should Read.” [As an aside, I really enjoyed her early book Wanderlust: A History of Walking.] Her opinion piece on Lithub is smart and funny, and she irked many readers; yet I do not see how anyone can argue with her final paragraph:

…that list would have you learn about women from James M. Cain and Philip Roth, who just aren’t the experts you should go to, not when the great oeuvres of Doris Lessing and Louise Erdrich and Elena Ferrante exist. I look over at my hero shelf and see Philip Levine, Rainer Maria Rilke, Virginia Woolf, Shunryu Suzuki, Adrienne Rich, Pablo Neruda, Subcomandante Marcos, Eduardo Galeano, Li Young Lee, Gary Snyder, James Baldwin, Annie Dillard, Barry Lopez. These books are, if they are instructions at all, instructions in extending our identities out into the world, human and nonhuman, in imagination as a great act of empathy that lifts you out of yourself, not locks you down into your gender.

Roth, Caine, Miller– “just aren’t the experts you should go to” if you want to understand half the human species; I love that tongue in cheek understatement. I also love her list of “heroes,” although it doesn’t hurt that she names among them many of my own heroes. She says she reads and re-reads work that she has opinions about–and admits her opinions may not align with the generally-accepted opinions. Which is fine, since she reminds us, quoting Arthur Danto, art can be dangerous, risky, uncomfortable, as long as it means something.

She does raise the point that “[y]ou read enough books in which people like you are disposable, or are dirt, or are silent, absent, or worthless, and it makes an impact on you. Because art makes the world, because it matters, because it makes us. Or breaks us.” In this way, she reminds us that readers are people who may have perspectives that vary from one another, particularly as to the social, psychological, or artistic merit of a piece of literature. Lolita, for example. That’s one book she mentions that evoked considerable response from Lithub commenters.

Rebecca Solnit’s response to her detractors–or “volunteer instructors,” as she calls them at one point–and her willingness to walk around the Himalayas with a medical team (recounted in a recent New Yorker piece) count as reasons her work has moved to the top of my to-read pile of books. I think I will start with Men Explain Things to Me and A Field Guide to Getting Lost.