I am not the sort of English enthusiast who makes a habit of ranting over bad grammar. I often feel annoyed at egregious errors; occasionally I go as far as to say “it drives me crazy when (insert common grammar mistake here),” but I understand that living languages change. Evolution is not just for finches, and stasis cannot be maintained in a complex system of human communication when technology and society and culture constantly create and destroy not only our environments but our methods of communication. Communication takes many forms and reflects the influences of many stresses, common usage being foremost among them.

Common usage may be verbally-based or textually-based or may depend upon references to popular culture or recent history, and it alters language whether we want it to or not. This fluid, flexible aspect of language fascinates me. As a poet, I relish it. As a teacher, I have to allow for compromise now and then.

I am willing to predict, for example, that very soon the accepted pronoun for words such as everyone and anybody is likely to be “they.” The reference was acceptable to Jane Austen and her writing peers, then went out of fashion in the Victorian era, when “he” became the norm–the word “he” is singular, as anyone is; thereafter, educated writers and orators used “he” for the nonspecific singular antecedent.

Of course, such use omits half of the population. Non-gender-specific writing employs “he or she” as the correct pronoun for words like someone. That usage leads to many a tortuous sentence, however. I generally advise my students to change the antecedent noun to a plural form whenever possible and to keep “they” as the pronoun; yet almost all newspapers, many news journals, popular magazines, and certainly most of whatever text appears on the web now employs the pronoun “they” for nonspecific antecedents. I don’t really have a problem with that–Jane Austen was able to make it clear enough whom it was she meant by “they.” Clarity’s what matters.

I do have a beef with the misuse of apostrophes, though. The apostrophe I’m talking about is a punctuation mark, not the poetic apostrophe which addresses someone or something absent or metaphorical. I mean the little superscript mark ‘ that is used for two main reasons:

1. To note an elision (the omission of letters)

2. To indicate the possessive case (barring the silly exceptions hers, theirs, ours, yours and its)

I understand the why behind a noticeable uptick in the number of times apostrophes go missing these days: texting, tweeting, and other shortcuts employed in social media communication. My students are vague about the comparatively simple rules of when to use the apostrophe largely because they never bother using it when they text one another. Furthermore, their customary “proofreader,” SpellCheck, doesn’t always alert its users to this type of error. Computer programs can recognize that dont is not a word, but cant means “sanctimonious talk” or, alternately, a tilt or slope (says Merriam Webster). It is a useful word, but it is not the elision for the word cannot. Furthermore, SpellCheck won’t (elision for will not; wont means habit or custom) be able to correct the typist who uses the wrong form of your/you’re or its/it’s.

Irksome, yes. But most mystifying to me has been the ridiculously frequent use of the apostrophe to indicate the plural. Surely no one is teaching our second graders to pluralize by adding ‘s to the end of a word. (Teachers who do so should have their certifications revoked!) Recently, when working with a student, I learned one reason this mistake crops up so often in my students’ papers: AutoCorrect. When the typist gets sloppy and tries to add an s to a word that takes a different ending for the plural form (puppy, puppies), AutoCorrect defaults to possessive case. The computer is too dumb to detect the difference, because this is English, and English is damned difficult.

I suppose another reason may be character limits for tweets and texts, but that seems less likely. If people don’t bother to use the apostrophe for elisions, why bother for plurals? “Susie got 2 puppys” conveys the same information just as incorrectly.

Proper use of the apostrophe in English is actually pretty simple–even though computer programs cannot quite figure out the two rules above–and clears up a host of potential ambiguities and misunderstandings. The world could benefit from communication that isn’t studded with misunderstandings.

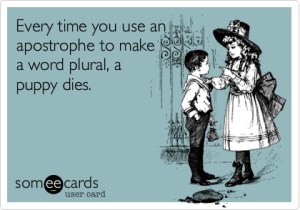

The warning below is one I use with my students. Sometimes, it even has the effect of becoming a useful reminder. Many thanks to the anonymous teacher who posted it on someecards.com.

•NOTE [Alas, just to complicate things, some editorial styles use the apostrophe to indicate plurals, but ONLY for letters or numbers, as in: “There are four 6’s in this statistical table.”]

•NOTE [Alas, just to complicate things, some editorial styles use the apostrophe to indicate plurals, but ONLY for letters or numbers, as in: “There are four 6’s in this statistical table.”]