Here’s James Delbourgo’s recent article in Chronicle of Higher Education (I read the Chronicle regularly, if that’s not already obvious) about collections of oddities. While the article itself is sometimes a bit maddening (what is his main idea here?), it put me in mind of Mantel’s The Giant, O’Brien and of collections my friends have accrued. Toshio Odate, for example, has some fascinating accumulations he keeps in clear acrylic boxes, and some of his art constructions feature curious things: a favorite of mine is a large frame displaying every pair of sneakers his son wore as a child.

Edmund de Waal wrote movingly about objects and collections in his book The Hare with Amber Eyes. Several months ago I promised myself I’d get back to the topic of objects and their stories, but it has taken me awhile to resume my meditations on the subject. As a child, I loved wandering slowly through the world, stopping and dawdling and picking up acorns, buttons, marbles, leaves, whatnot. Sometimes I would arrange these found objects into tiny houses, or float them on puddles, or arrange them on my windowsill. I might imagine stories around them, drawing on Andersen’s “Thumbelina” or the song “Froggie Went A-Courting.”

“Swiss Shoot the Chutes” by Joseph Cornell

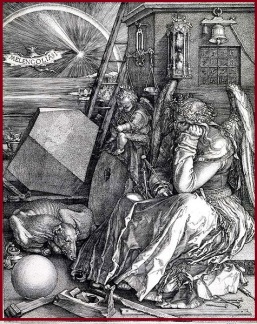

Not too many years later, when I encountered Joseph Cornell’s work, I was enchanted. His boxes contained mysteries, stories, possibilities, and fears; and they were achingly beautiful to me. Not unsurprisingly, Cornell’s work gets a mention in Delbourgo’s piece, which is partly a review of Brian Dillon’s book Curiosity: Art and the Pleasures of Knowing.

From the Chronicle essay:

Curiosity, Dillon proposes, is a way of knowing that looks askance. It draws attention to the unexplained or overlooked fragment, to invite us, if possible, to look sideways and look closely at the same time. As such, its promise of knowledge is ambiguous. Does curiosity seek to unmask the strangeness that absorbs its attention, or is it an invitation to luxuriate in that strangeness? Does it carry an inherent Baconian injunction to go further and illuminate, or does it recommend the alternative pleasures of not knowing?

I like those inquiries and feel they may inspire some poetry. Later, while considering the way some collectors, particularly wealthy or scientifically-minded ones, made detailed lists of the oddities, Delbourgo notes that

Dillon suggests that such lists also constituted “a kind of story,” but do they? The list is an open form, not a closed and completed one. Curiosity collections could absorb countless new objects precisely because they didn’t propose a coherent narrative about them. Unlike spoils that tell of conquest, curiosities don’t preach and don’t teach. What makes them curious is their oblique relation to the world in which they’re embedded. And yet, as a matter of historical fact, early-modern Europeans accumulated curiosities in no small part through trade, colonization, and war…

The 18th-2oth century ascendancy of science and the current trend of interdisciplinary art-tech-science aesthetics gets a mention in the article, too:

Curiosity and wonder—distinct terms but often used interchangeably—turned out to be interwoven with theology, civility, craftsmanship, nature’s playfulness…Curiosity thus helped dethrone the modern fact from its hegemony over the history of science.

Again a connection with de Waal, and also with the work my brother has been doing in reconsidering the skull collection of Samuel Morton (and other early modern anthropological collectors). In the case of many people who collect ‘curiosities,’ there are thorny questions of ethics vs. the ‘value’ of extending knowledge or awareness. The political, the legal, the ethical–these can conflict with curiosity in many forms it can take, from the problematic Rauschenberg sculptural combine “Canyon” which features a stuffed bald eagle, to the superficial thrill that gets us to sit through an adventure movie even if we can guess the ending.

Curiosity is basically an exploratory response, as psychologists term it, which covers a vast arena of animal and human perceptions of the environment to orient us to potential situations and to prepare us for behavior/action. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, D.E. Berlyne studied what I call curiosity quite extensively, including some exploration into art and aesthetics though mainly concentrating on the reactive responses that make us susceptible to enjoyment or evaluation of art, humor, literature. (He published, in 1954, A Theory of Human Curiosity, which I think I must read after I read Dillon’s book).

But now I am drifting far from my topic of stories and objects. Probably that’s Delbourgo’s influence, as his essay wanders a bit, though the author cites some books I plan to add to my to-read list; for that, I am grateful, but I would prefer to look at how objects inspire stories, or make the need for stories. There’s the sun in the sky each day, and it leaves each night. We make up a story about that, or about why the leopard has spots or why there are stars in the sky.

Here’s something from my own collection of curiosities, a wooden ampersand from an antique type magazine.  And there’s a story I could tell about it which would be more or less ‘true,’ but there are better stories yet to be invented.

And there’s a story I could tell about it which would be more or less ‘true,’ but there are better stories yet to be invented.

Or, tell the story of Cornell’s “Observatory Box.”

“Observatory Box,” Joseph Cornell