Recently, I listened to a radio interview with Madeleine Albright, former Secretary of State, who is promoting her latest book. The interviewer asked her what quality she thought most crucial to a good leader. Albright has met many, many leaders; she is also a brilliant person. It was a good question to ask her, and she had an excellent and thought-provoking answer: A good leader should be confident, but not certain. (If you download the mp3 file in the link above, her explanation of this idea comes near the end of the program.) Powerful people who are both confident and certain of themselves, their aims, knowledge, and ideas, are too likely to veer into autocratic dictatorship. Those who are neither certain nor confident are too easily swayed by advisors with their own agendas or are unable to make decisive moves. A person who is open-minded–and therefore not certain–but who is confident in his or her ability to make a good decision once the facts are in, leads wisely and well even when mistakes occur due to faulty information or circumstances beyond anyone’s control.

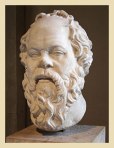

We could all benefit from becoming more confident and less certain. It strikes me that Socrates might have possessed this pair of qualities. The philosopher continues to question and is therefore not certain; but the uncertainty isn’t of the waffling, inconclusive kind. Uncertainty in Albright’s use of the word means curious, inquisitive, searching. The confident person trusts his or her values (confidence, from fidere, “to trust”) but does not let dogma or single-perspective “certainties” obscure research, facts, other perspectives.

I will grant that this approach is difficult for us humans, and that is why so few leaders possess this pair of traits. While I have no interest in becoming a world leader, I plan to keep Albright’s phrase in mind and discover whether I can become more confident and less certain in my life.

This bust resides in the Louvre, and the image was found here: http://www.humanjourney.us/greece3.html

~

Gardening is one area that relates well to confidence and uncertainty, though in a slightly different form of practice. I’ve been a gardener for over 30 years, and one thing you learn when you garden is that there are no certainties. Planning takes mental and physical effort and preparation, and then there are the endless obstacles involved in planting and overcoming soil deficiencies, insects, fungi, and weather inconsistencies just to name a few. Am I a confident gardener? Yes. Years of research, experiment, study, practice, trial and error–and successes–have made me confident. But there are always new hybrids to try, new species to plant, and there are problems that never seem to go away (why can’t I get carrots to grow here, when I have grown carrots every other place I’ve lived? How to keep certain fungi at bay using organic means?).

And one never has any sort of surety or pledge (the etymology of “certainty”) that those tomatoes will ripen without blossom end rot or fusarium wilt, that the pigweed will not take over during the gardener’s five-day vacation (well, that’s almost a certainty!), or that hail will not wreck the whole summer’s worth of plantings.

This year, my vegetable garden is producing well despite overbearing heat, hard brief rains, and far too many weeds. I feel annoyed with its overgrown appearance, but one thing about gardens is you get another chance as long as you can wait a couple of seasons.

Meanwhile, with a little more thought and research, I’m confident I can plan an even better garden next year.