Despite pandemic restrictions, or perhaps because of them, I have been blessed with poetry the past few weeks. I have attended workshops and readings remotely/virtually, and I’ve participated in a few of those as well as giving one in-real-life poetry reading. I signed up to get the Dodge Poetry Festival’s poetry packet & prompts, and those appear daily in my email. Best of all, poems have been showing up in my mind–I started quite a few drafts in April.

Up to my ears in potential manuscripts (I have at least two books I am trying to organize), I’m also waiting rather anxiously to see whether my collection The Red Queen Hypothesis will indeed be published this year as planned. The virus and resulting lockdowns have interfered with so much. The publication of another of my books matters to me, but it remains a small thing in a global perspective, so I try to be patient.

Meanwhile, I thank poet Carol Dorf of Berkeley CA, who has been kind enough to read through one of my manuscripts and offer suggestions. It’s such a necessary step, getting a reader. I recently enjoyed this essay by Alan Shapiro in TriQuarterly, in which the author reflects on his many years of poetry-exchanges (he calls it dialogues) with C.K. Williams. His words reminded me of my friend-in-poetry David Dunn, who was, for close to 20 years, my poetry sounding board, epistolary critic, and nonjudgmental pal who often recognized what I was going for in a poem better than I did. Shapiro says he feels Williams looking over his shoulder as he writes, even after Williams’ death (in 2015). In a section of the essay Shapiro has an imagined (possibly?) conversation with a post-death Williams, conjuring the remarks his friend might have made in life, or after. I have had such dialogues with David, but not recently. It may be time to try again. Or, as Williams told Shapiro before he died, “Find a younger reader.”

As if that were easy.

Anyway, I continue to learn new things, even things I did not feel particularly curious about, such as Zoom teaching [blech!] and Zoom poetry readings and remote workshops and online discourse. Hooray, new skills to practice! Here’s a taped reading in which I read a few poems from Barefoot Girls, The Red Queen Hypothesis, and a couple of newer pieces. I appear at 31:48 on this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HFfeoTOVahQ

Though I think you should also give a listen to the other poets, who are worth hearing.

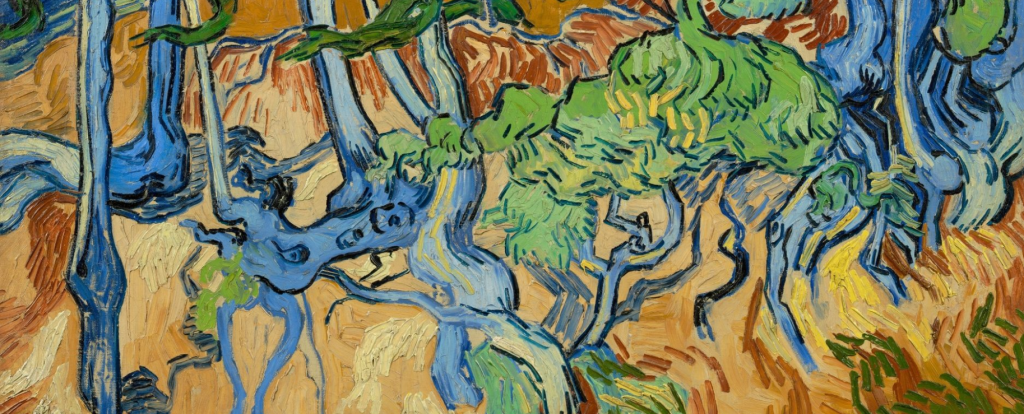

Time to weed the lettuce and spinach rows, time to stoop to smell the lily-of-the-valley. And time to have imagined discourses with my Beloveds.